Montreal, 1981

In the middle of bringing dishes of unidentifiable delicacies to the table, she stopped and frowned.

Oh, I’m sorry, I’m all out of yoghurt, she said.

That’s fine, I blithely replied, wondering why yoghurt was so important all of a sudden.

As a child in Montreal, I had admired Indian ladies in saris – the only people who genuinely looked like they came from somewhere else. But Roli was the first Indian I had met personally – in a political science class, where we ended up studying a revolution together. As a way of getting to know each other, she had invited me to my very first Indian meal, somewhat of a revolutionary step for the sheltered 18-year-old I was then. Hence my ignorance about the significance of yoghurt.

My native food culture, as it happens, has of late become famous for its thick, creamy yoghurt. We eat it as a snack or dessert, often with honey, or use it to make tzatziki, a cucumber salad. But it’s a much more marginal component of a meal than in it is in India. That first Indian meal was the first of many occasions I would have to compare our food customs, to wonder whether they could reveal something about our respective ways of putting the world in order, and to observe the ways in which the world at large changed them both.

I don’t remember what my new friend cooked that day. What I remember was how shockingly hot everything was, and how she burst out laughing at the face I made when I bit into a whole chili before she could stop me. I had never felt my mouth catch fire in this way. As I reached for the water – not yet knowing that water is no help – she declared: “THIS is why we needed yoghurt!”

That was decades ago. Since then, I have travelled to India several times, eagerly trying every new dish presented to me; I have an inkling of what dishes to seek out in Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai or Chennai (or even Lucknow, though I have yet to go there); I’ve been invited to Indian home meals, enjoyed vegetarian feasts at weddings and pujas, and have ventured fearlessly into street food stalls. I’ve also invited many a friend to my own Indian dinner parties.

And yet, I wonder. Do I really know any more about Indian food than a curious tourist does? Is it possible to come to any cuisine as naturally as to one’s own, or to delve in as deeply? And just what do we mean when we say “Indian,” or indeed “Greek” food, anyway?

India, 1986

Laura looking mournfully at her plate in the New Delhi YMCA : “This fish died for this.” I had to agree with the sentiment. We had got used to well-cooked meals at the YMCA. The fish on our plates was also well-cooked. It was the recipe we objected to. Such heavy spices in a fish dish felt to us like a misunderstanding of the nature of fish rather than an excitingly different way to cook it. And it was too damned hot to eat anyway.

I had decided on a whim to join my college friend Laura who was travelling in Asia, and had steered her towards meeting me in India. In Delhi. In May.

Nothing could have stopped me from finally going to India. Reports of extreme heat hadn’t fazed me; I told myself I come from a hot country too. I was wrong. The blast-furnace intensity of the north Indian summer was scarily new, as new to my skin as the hot chili had been on my tongue in Roli’s Montreal kitchen. I had somehow forgotten that, in Greece, only mad dogs and tourists went out in the midday sun – and now, embarrassingly, I was that tourist. But in this wilting heat, eating felt less a pleasure than a necessity. I found myself wondering why a country this hot would even bother developing an elaborate cuisine. All I wanted to do was guzzle as much liquid as possible. I overdosed on hot tea and lukewarm Limca. On the second day we nixed our plans to see Varanasi and decided instead to head for the hills. Alas, so did everyone else who could afford a ticket. We sat for hours in the Indian Airlines office, the only option in those distant pre-privatisation days, hoping to book a flight to Kashmir. Finally, the clerk looked up: There’s nothing for Kashmir. Why don’t you go to Darjeeling instead?

So, we did. The cool air revived us; the tea was ambrosial; the food on our plates, like everything else around us, started coming back into sharper focus.

In a rickety outdoor café, I had my first chola. Did I recognize it then as chickpeas, or did I take it to be another vaguely familiar variety of pulse? Did I think to ask whether it was a Himalayan dish or an import from the plains? All I remember is that I had to stop myself from ordering seconds. A song played in the background; I asked who the singer was, and later went out and bought a cassette. Whenever I eat chola, I mentally accompany it with Pankaj Udhas singing La Pilade Saqiyah. Later, in another rickety café, I had my first truly local dish, momos. These I downed while reading an India Today article about MS Subbulakshmi. (I went out that day and bought a tape of hers, too; momos and Kritis have been welded in my mind ever since. Musical and culinary associations don’t always make sense. )

When I got back home, I bought my first Indian cookbook.

Cooking Indian, or should that be “Indian”?

A French cook, we’re told, can turn out better Chinese food in China than a Chinese chef in France. The phrase is meant as a comment on the importance of local ingredients. But that isn’t the half of it. When cooking Indian food in Greece, I don’t just lack the rarer or more perishable Indian ingredients; I lack an Indian environment.

Cooking food you haven’t grown up with is an act of gastronomic arrivisme. My guests were on even shakier ground. They had not been raised on the recipes I was putting in their plates, had no knowledge of what was expected of the cook or the guest, could not tell whether our local prawns or aubergines replicated the taste of Indian ones, were blissfully unaware that the prawn dish came from the tropical Malabar coast and the aubergine dish from the edge of the desert, and would have reacted to an absence of dal the way I did to the lack of yoghurt at that distant first Indian meal: so what? All the same, my dinner parties were popular, with people clamouring to be invited. As I had only learned to cook well into my twenties, this success was a feather in my cap.

My misplaced pride was shattered when I first served Greek food. As I listened to the sighs of contentment and requests for seconds or thirds, the penny finally dropped. Much as my friends had enjoyed my Indian pantomimes, this modest spread of spinach pie and pork-with-onions was much more meaningful to them. Had they all along been thinking “This exotic bhindi dish is nice, but not a patch on my mom’s okra,” I darkly wondered. The whole thing suddenly took on the aura of firangis wearing saris — an essential garment transformed into fancy dress, an isolated cultural specimen reduced to decoration, like the lovely sculpture of Saraswati I had bought in Bhubaneswar and placed in my dining room, where the goddess stood unrecognized, unadorned and unworshipped.

But did it matter? Must a statue be worshipped to be appreciated? Must a cuisine be known in depth to be enjoyed? Is it not presumptuous to ask for more, to try to understand a culture through its cooking? Is there really any deeper meaning to the fact that a Greek dish of lentils includes nothing more than garlic, bay leaf, tomato and olive oil, while Indian dals involve elaborate temperings and spice combinations?

Perhaps there is. In the past few years, I’ve given fewer dinner parties, though I often cook Indian food for myself. But something unexpected happened in the pandemic: I started using my spice cupboard less. My pulse dishes were as likely to be Greek lentil soup or blackeye bean salad than rajma chawal. My vegetable dishes moved closer and closer to the Mediterranean. It took a crisis to show me that I had overestimated the extent to which Indian food was comfort food to me.

Or perhaps my change of location was to blame. During the lockdowns I had come to the countryside to live with my mother; and it was there that I started asking myself why I was flavouring my green beans with panchphoran instead of parsley from the garden. Using ingredients shipped across thousands of miles suddenly seemed profligate and silly, when alternatives to my carefully stored spices were literally growing on the trees shading my bedroom window, or in my mother’s erratic herb plot, or else were piled high in the local farmers’ market.

Was my dabbling in the cooking of a different culture – and thus of different flora and climate – just another symptom of urban consumerism?

At times I resolved that we should all just cook what our elders had fed us, what our landscapes and customs created, and forget about the latter-day afflictions of convenience, speed, and aspirational food-travel. But my memories of long-lost orange varieties and the vanished aroma of what are now called “heirloom” tomatoes sounded a Heraclitan warning: you cannot walk into the same cuisine twice. When even the seeds are controlled by a handful of multinationals, when the wood-burning earthen oven under the vine arbour has been replaced by the electric cooking range in an apartment, how can we think of reviving our grandmother’s food? And why are we so inclined to leave her own back-breaking work out of that idyllic picture?

The younger generations may not think much of our traditional kitchens anyway. A recent Greek ad in which a teenager, upon being told that her mother is cooking chickpeas, decides to order pizza instead, would be unthinkable even ten years ago. But in an age where dozens of food-delivery motorbikes clog the streets, housebound computer workers order their morning cappuccinos from coffeeshops and it is rumoured that some busy parents have hamburgers delivered directly from restaurants to their kids’ schools, it seems spot on.

What were Indian middle-class children growing up with now, I wondered. Was it home-cooked food? Was it what Santanu – who produced wonderful Bengali food in his Kolkata kitchen – derisively called “Hindu fast-food”? Or was it mostly just the same awful fast food that is foisted on the rest of us?

One clue came from my last trip. It was full of wonderful food: Marathi vegetarian thalis in a family restaurant, silky keema at a corporate event in Pune, Durga Puja feasts and late-night phuchkas in Kolkata, bhelpoori on the beach, seafood curries and Gujarati vegetarian masterpieces in Mumbai. Yet one of my strongest memories is not of these exquisite treats. It is of the young mother in the Rajdhani train who fed her six-year-old potato chips for breakfast – after allowing him two such packages in the evening, on top of a cooked meal and various sugary treats.

What poor person can afford to stuff their kids with potato chips? The overweight thronged the malls and airport lounges, discussing real estate and private schools. Their drivers and domestics, the fruit sellers and construction workers, were mostly slim and sinewy. In this world, having an obese six-year-old who gets winded just from playing in a train compartment might become something to aspire to.

It’s no challenge to find such six-year-olds in Greece. Photographs of families at the beach, taken over the past few decades, reveal the expanding girth of children and parents alike, and children are rarely denied treats – a collective memory of malnutrition and hunger, an underlying fear that present affluence could disappear overnight, is still affecting us. But the overweight in Greece tend to be working class. Ever-longer work and school days have meant more grazing and fewer common meals. Farmers’ markets thrive, but they belong to the pensioners, the grandparents, some of whom actually do the cooking for working families. The gainfully employed shop hurriedly in supermarkets, piling their trolleys with packaged products, arguing with their children over the candy displays at the checkout counter.

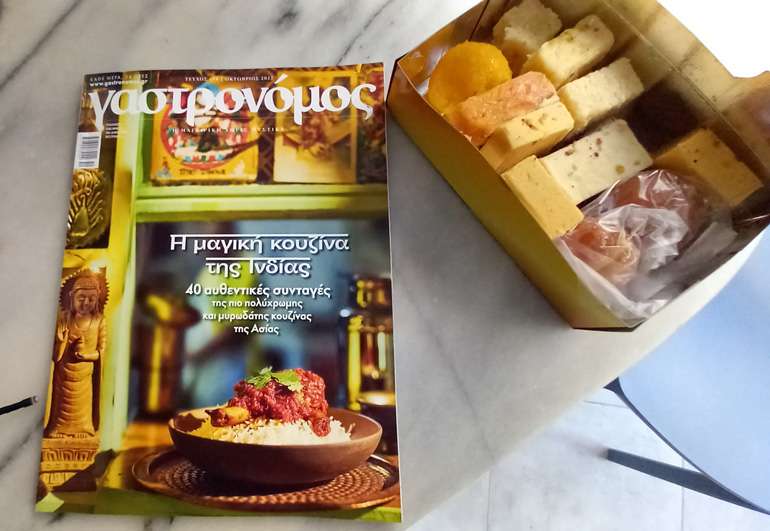

This week I spotted something else at the checkout counter: a new issue of the leading Greek magazine of gastronomy with a cover story on Indian food. I snapped it up at once and started reading with the possessive suspiciousness with which one approaches a foreign publication’s coverage of one’s own culture. I was relieved to find that the editors had solicited information not just from restaurants but from Indians living in Athens, cooking for their own families. I smiled contentedly when I found a separate section on dals. I clucked in disapproval when an interviewee said sixty percent of Indians are strict vegetarians – where did that number come from? I snorted derisively at the fake-Devanagari font. I beamed at the lush photographs of some of my favourite dishes. I diligently took down the addresses of specialty shops. I basked in the knowledge that Athens had finally acquired a dosa place.

What had happened to my resolutions to cook local? Where had my earnest questions about the nature of national cuisines and food tourism gone? Up in biryani-scented smoke!

No, I don’t think I’ll ever stop cooking Indian food, or pining for the real thing.

Tussling with Indian cooking has made me understand at least as much about my own culinary habits and assumptions than French or Italian food have. After all, Greeks and Indians share certain traits absent from Western Europe: we both prefer shared dishes to separate courses, and we both consider vegetables and pulses a centrepiece of the meal, or the entire meal, rather than a side dish. Both schools of cooking also exhibit the quality I most admire: the ability to make highly-flavoured dishes out of ingredients that are not in themselves flavour-intensive. (If you can coax as much savour out of dal and millet as that unforgettable Gujarati restaurant in Mumbai, to my mind you’ve achieved something much more difficult than building a meal around high-umami ingredients like truffles or sausage.)

I’ve now made my peace with the fact that I’ll only ever be a visitor to Indian cuisines. (Cuisines, plural: and one thing I have learned is that a culture cannot be reduced to a hypothetical national cuisine, because in lived local experience there is no such thing.) That the best you can do is to approach any foreign cooking humbly, aware of the vast swirling constellation of social and cultural realities and ideas the simplest dish may represent. The best you can do is enjoy it.

Years ago, I came back home from my South Asian Studies course in London (where I was often asked “A Greek studying Indian history? How come?” Nobody ever asked that of the Britons or the Germans) with a box of Indian sweets for my parents – barfi, gulab jamun and carrot halwa.

My father, the family gourmet, pronounced them unpalatable. “This tastes like soap,” he said of my beloved pista barfi. Indignant, I resolved never to bring him anything new again. He clearly didn’t deserve it!

The next day after lunch, as he was making his coffee, my father said, “I wouldn’t mind a little more of that soap.”

Brilliant!

What a wonderful piece of writing.

Extremely interesting reading . Read your comments on the Foodies , Goa with great interest . As a 6 months a year Goa resident one has discovered so many , places , igood food and hope to meet many interesting fellow foodies.